Flowing through Time and Tradition

Water sustains all life—but its significance goes far beyond survival. A gentle yet powerful force, water flows, wears down rock, and carves new paths. It shifts between states of matter and forms—calm to turbulent, held in a cup or reaching unexplored depths. Water nourishes and destroys, divides and connects. Its presence—and its absence—shapes landscapes, cultures, and life stories.

Exploring the theme of water through the holdings of the Magnes Collection, this exhibition traces how water flows through and shapes Jewish lives: enacting belief, sustaining life and communities, providing the means for spiritual cleansing, and mapping identities.

Through the complex nature and symbolic power of water, we invite you to reflect on the forces that shape how we live, think, and relate to one another.

The exhibition, Flowing through Time and Tradition, includes 65 objects—sculptures, textiles, photographs, paintings, prints, rare books and manuscripts—dating from the 16th to the 20th century, and originating from over a dozen countries, including India, Cyprus, Russia, Israel, Belgium, Syria, Egypt, and the United States.

Believing

Droughts, rainfall, floods, morning dew, storms, and rising seas. Some view water’s power as expressions of the divine realm. Jewish liturgy, biblical texts, and religious writings depict water as both a source of life and of destruction—as reward and as punishment—with a role for human prayer and intervention.

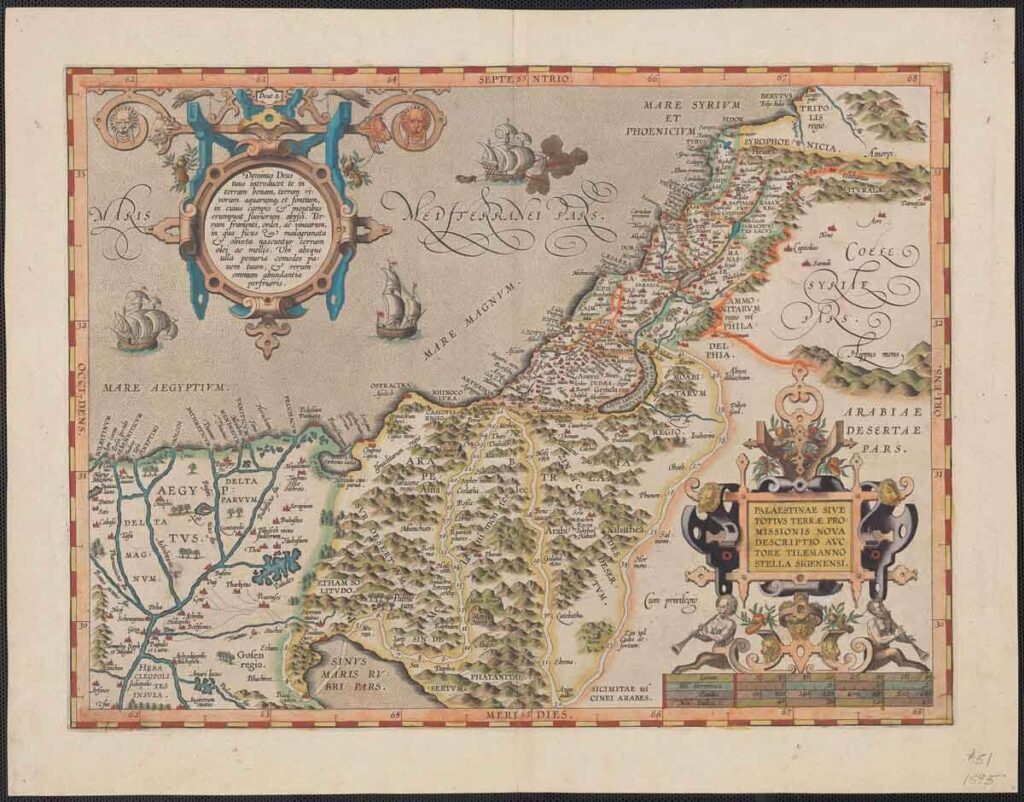

Abraham Ortelius (1527–1598), Palestinae Sive Totius Terrae Promissionis Nova Descriptio Auctore Tilemanno Stella Sigenensi [New Representation of Palestine or All the Promised Land by Tilemann Stella of Siegen] Antwerp, Belgium, [1595]. Gift of Toni Weingarten in memory of her father Max Weingarten, 2013.1

Sustaining

Accessing water often requires great effort, from digging wells and building dams, to redirecting rivers. Its presence doesn’t guarantee cleanliness or abundance. As a vital yet limited resource, water symbolizes both struggle and hope, and reflects human relationships. In biblical texts, flowing water represents deliverance, and the way it is shared expresses one’s character.

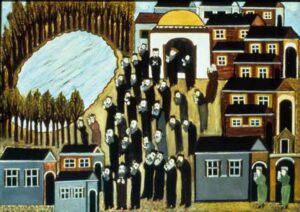

Maurycy Minkowski (1881–1930), Refugee Children, Poland, 1900 – 1930. Oil on canvas. Gift of Dr. John Rayn, 77.331

Cleansing

Across many cultures, water facilitates experiences of spiritual cleansing. In Jewish tradition, water-based practices help a person transition from a state of spiritual vulnerability (tameh)—often brought on by contact with illness or death—to a state of spiritual wholeness (tahor). These water rituals reflect the rhythms of life, offering moments of transition, healing, and renewal.

Natan Heber (1902-1975), Tashlich, Israel, ca. 1970, Oil on wood. Gift of Jacques and Esther Reutlinger, 83.54

(Dis)Placing

Bodies of water divide and connect, serving as boundaries and routes of exchange. Throughout history, water journeys have meant travel, trade, war, exile and homecoming. These movements of history result in more than physical relocation, they are personal journeys. For the Jewish people, bodies of water serve as unique identity markers, and crossing them plays a central role in both origin stories and individual histories.

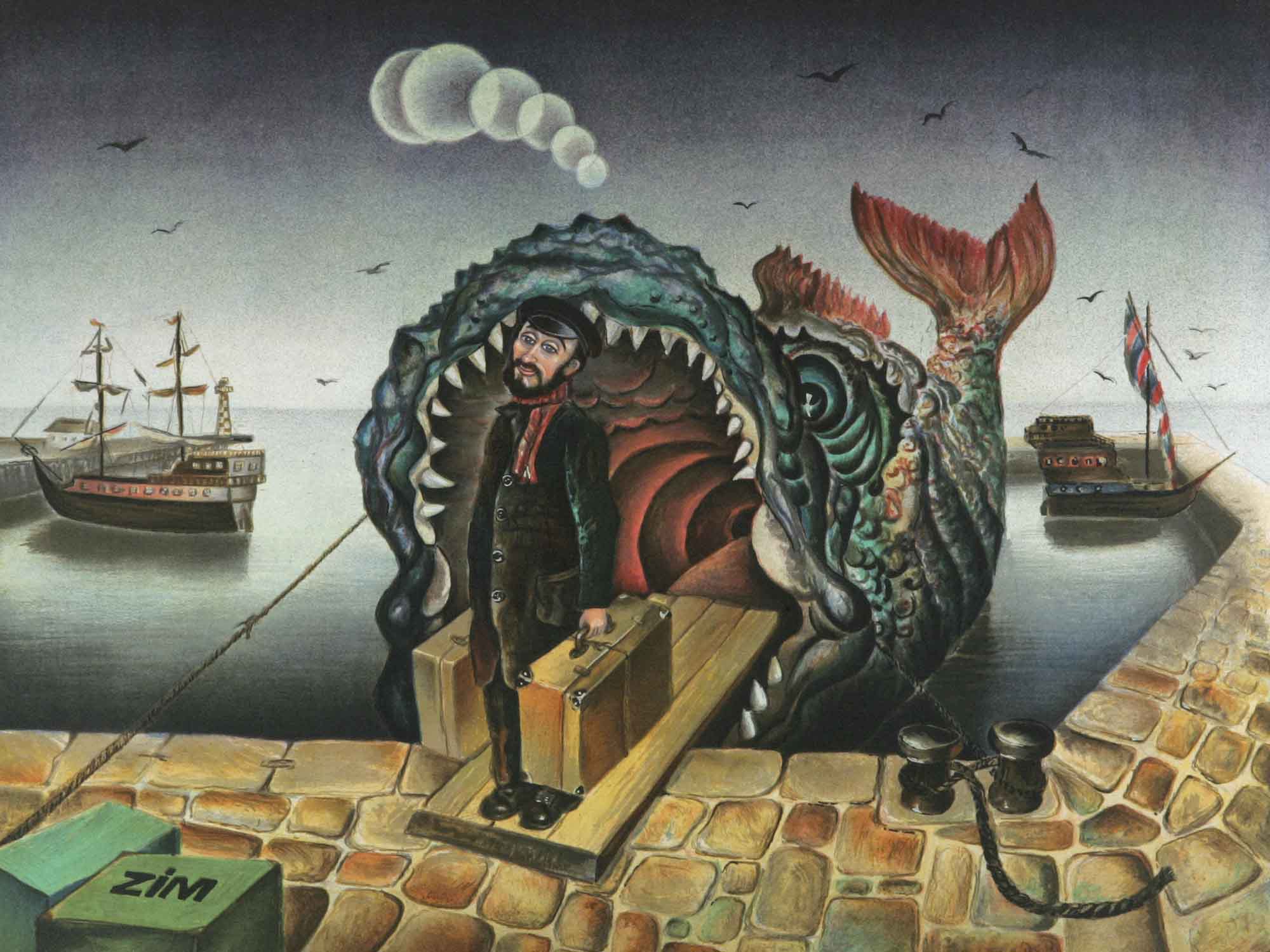

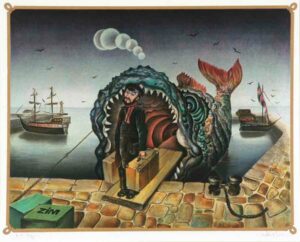

Eugene Abeshaus (1939-2008), Jonah and the Whale in Haifa Port, Tel Aviv, Israel, 1978, Color lithograph. Gift of the artist, 94.26.3

Image at top: Jonah and the Whale in Haifa Port by Eugene Abeshaus (1939–2008), Tel Aviv, Israel, Grebel, 1978. Gift of the artist, 94.26.3.

Curator:

Achinoam Aldouby

Registrar:

Julie Franklin

Assistant Registrar:

Andrea Calderon

Head Preparator:

David Sullivan

Preparator:

Jennifer Cole

Design:

Carole Jeung

The curator thanks Laura Lerman, Rena Fischer, Dan Alter, Laura Bratt, Tina Kremzner-Hsing, community focus group participants, and the Teens Take the Magnes Committee, whose feedback and ideas helped shape the exhibition.